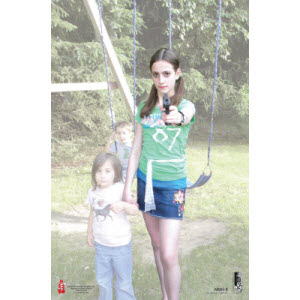

Off the topic, has anyone seen the "no more hesitation" targets being supplied to the Government? Like something that would be supplied to the "Einsatzgruppen". They are disturbing on a visceral level. Unlike all other official government products, they are uniquely non-diverse. Just an oversight, surely. Love to hear your comments on them, Grim-they represent a sort of "anti-chivalry".I have heard of these products, and seen them. You can read about the controversy here and here. Let's look at a few of them, and then I'll give you my thoughts.

These targets are for law-enforcement training, and are called the "No More Hesitation" series. The company confirmed the intention was to train police not to hesitate to shoot these kinds of people. It's also clear why that might be important: hesitating to shoot someone who already has a firearm pointed at you can get you killed. Thus, this series exists to help police practice shooting people with guns pointed at them even if they happen to be pregnant women, children, little girls standing next to their even smaller brothers, and so on.

Training to kill such people must be undertaken with a very serious mind. I can give a case when killing such a person -- without hesitation -- might be appropriate: but it is not a policing case. It is a case from war. If you are operating against the kind of enemy that brainwashes children, or uses pregnant (or apparently-pregnant) women as suicide bombers, you may need this kind of training. In this case an enemy is relying on your humanity to give them a window to conduct a high-casualty attack. Sadly we have seen this in places like Iraq and Israel, so it is a consideration we have to take seriously. If a quick kill is necessary to prevent the detonation of such a weapon, and if such a detonation would injure more innocent people than the child you are killing to stop it, then it might be justifiable.

Killing pregnant women or children even in those circumstances is a serious moral crime. However, in that special case, the crime is not yours. It belongs to the men who bent the weak to their evil will.

However, that special case does not seem to include the intent of these targets. The above article includes a comment from a reader, who points out that most of the series has people inside their own homes -- wearing night-dresses and so forth -- who are pointing guns at the police officer. Now this seems to be exactly the kind of case in which hesitation is most appropriate, as these people have a legitimate right to have a handgun and to be responding with it to an intrusion. De-escalation training is surely what is needed here: to try to find a way to walk the situation away from where shots get fired at all.

If instead you are training to shoot without hesitation, what you are doing is dishonorable. To honor is to sacrifice, of yourself or your possessions, for something or someone you value more. Honor is the quality of a man who does this.

The path of honor in a case like this is to hesitate, to make the sacrifice of taking the risk onto yourself instead of making the child bear it. The purpose of the strong is to protect the weak: it is the reason you were given strength. You should hesitate long before you kill a child to save yourself, or a pregnant woman, or the elderly. Anyone who cannot see that is dishonorable, and unfit to bear arms.

An organization that teaches the strong to protect themselves at the expense of the weak is evil. It should be disbanded, replaced if necessary but with an entirely new organization, with a new corporate culture and no members who were associated with the decision to execute this kind of training.

At this time, of course, we only know that this product line was made available -- we do not know which agencies or forces undertook to train with it. We should push to find out, and remove anyone who thought this was a good idea from public service.

Those are my thoughts, since you asked.