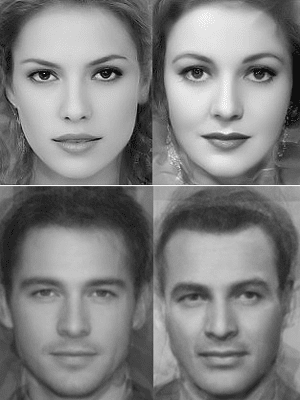

Following up on T99's earlier post about feminine beauty, a post on facial averages for Hollywood celebrities. The results are unsurprising to anyone who watches movies.

What is more surprising to me is this:

The average golden age actress comes from this set:

Who's missing?

Maureen O'Hara. I thought this "average" was built around her: but it turns out she wasn't even included in the sample.

Striking

Chart-toppers

Chart-toppers

Chart-toppersSomeone has collected 5-second snippets from every #1 Billboard Hot 100 hit from the system's 1958 start through 1992. I'm too young for the very earliest hits, a few of which don't sound all that familiar (except for the regular intrusions of Elvis classics, of course). About the time the Beatles show up, February 1, 1964, with "I Wanna Hold Your Hand," it seems that every third song is theirs. This part I know quite well, through about the mid-80s. Rather suddenly, I'm recognizing only every tenth song; the rest just sound like generic 80s movie soundtracks. By the early 90s, I'm recognizing every 20th song, apparently having tuned out thoroughly by then.

It's strange how out of order some of these seem. I never would have guessed that "Do Wah Diddy" hit #1 at about the same time as "The House of the Rising Sun." They seem in memory to belong to different decades. "My Girl" and "Eight Days a Week" were from the same month? And both predated "I'm 'En-er-y the Eighth, I Am"? That Herman's Hermits album, by the way, was the first I ever purchased, at the age of nine.

A full list of the hits by year is here. Is it just me, or did something really awful happen in 1974? I like about three songs on that list, but the rest give me hives.

H/t Brandywine Books.

The Saga Of Biorn from The Animation Workshop on Vimeo.

Female Beauty

Female Beauty

Female BeautyMaggie's Farm had this link to a Geekologie site with composite photos depicting the "average" face of women of a number of ethnicities. The program produces faces of quite remarkable beauty. Of the dozens of examples, I found that the average French face seemed the most familiar or "American" to me, while the Uzbek face was by far the most beautiful.

Psych Phot

This makes for interesting reading: an account of a man who could make Polaroid pictures with his mind. There's an account of the attempt by skeptics to prove he was faking (none of which succeeded); but the author is credulous.

What is most striking about the Serios thoughtographs is the power of their imagery as a manifestation of the creative process. In these strange pictures, real objects or places appear to have merged with (or been altered by) the material of Serios's unconscious. Some of them juxtapose target images (of familiar buildings, monuments, houses, and hotels) with what appear to be images of day residue, haunting shadows of unfamiliar forms and structures. Others seem to incorporate both past and future events in an odd, shadowy collage. On one occasion, for example, the target image appeared superimposed on a second image that resembled the space probe Voyager 2. After the session, Serios, a space buff, confessed that he had been preoccupied with the progress of the space mission at the time and was unable to clear it completely from his mind.This seems to run afoul of a few different problems. Does philosophy contain anything that might explain them?

Other images could have been obtained only as a result of knowledge or perspectives unavailable at the time. For example, after seeing magazine photographs taken from Voyager 2 of Ganymede, a moon of Jupiter, Eisenbud suddenly recognized some of Serios's previously unidentified thoughtographs as images of the moons of Jupiter. That made sense, as Serios had long been obsessed with Voyager 2; what did not make sense, however, was that those thoughtographs had been produced years before the Voyager 2 pictures were taken. He also occasionally produced pictures that would be possible only from a midair perspective, including an exposure showing part of Westminster Abbey, and an image of a Hilton hotel in Denver.

Well, yes, actually it does. Space-time persistence theorists believe that -- in spite of our experience of 'living through' time -- we are in fact a static, four-dimensional object, extended in three physical dimensions plus time. Something that was significant to that object "later" is still a part of the single object, in the way that one face of a cube is still part of the same cube as the opposite face. I know a doctor of physics and metaphysics who is quite certain this is correct.

I'm not convinced, myself. Without going so far as persistence, you can still argue that the mind can move freely in the four dimensions: for example, how many of us have sat in our chair at work on Monday morning and imagined being at a cookout the previous Saturday? Your conscious mind can readily "image" that time and place for you; it may be that your unconscious mind can reach forward. It may not be reaching for a certain future that you 'already inhabit,' as the persistence theorists believe; perhaps it is only reaching to a likely future.

Or possibly it's all bunk; but how then to make an image of Voyager's pictures of the moons of Jupiter years before anyone has seen them?

Cuts

Reason offers an analysis of the current political situation, with a one-step solution.

We may not be France yet, but there are disturbing signs that Americans may be ready to take to the streets angrily in defense of their government deals and giveaways. (Some polls showing a lack of support for the very idea of public employee unions are encouraging, but it doesn’t take a majority to cause civil unrest.) Wisconsin may be the first sign that, no matter how much support one can gin up for shrinking government, actual attempts to restrain a free-spending government will be met with strong political counterforce—even when that interest is overpaid teachers and big-money unions.All politically possible cuts must be supported. That's interesting, but it is not a solution to the current problems.

The threat of federal government shutdown, happening simultaneously with the Wisconsin crisis, demonstrates that the fiscal crisis is multileveled, and no one wants to allow it to be dealt with seriously....

The only really serious position moving forward about government size and government spending is how to cut it, and how soon. While the fight to cut specifics here and there may seem ugly and unfair, all cuts need to be supported, wherever they seem politically possible.

By this I do not mean that it isn't a good idea: in general, it probably is. The easiest way for a cut to become politically possible is if it is a Republican priority (say, a new engine for the F-35). While in the short term that means a government that is only executing the program of the left, it leads by example, and more importantly, it refocuses the minds of the party of the right on the question of cutting, not spending.

Even so, the runaway problems are three:

1) Medicare,

2) Medicaid,

3) Un- and underfunded retirement benefits, including Social Security, government pensions, and government health care plans.

Here is a chart showing the explosive growth of these three types of problems. This is not new; we've been talking about unfunded pensions here since 2007. My thoughts back then pretty much echo my thoughts now: the political system will not be able to address cutting these things, which means that the cuts will come in the form of systemic collapse. That means a kind of tribalism, not solely based on blood ties, but on ties of kinship and friendship.

Well, and that was the old system: and mostly it worked. Sometimes it didn't, which is why Social Security was a popular idea. Nobody wanted a situation where elderly people were dying in the street after a lifetime of work.

A bigger problem, though, is that our economic system has changed in fundamental ways over the last sixty years. The capitalist system of the 1950s assumed that everyone would be a jobholder, because there was so much labor that needed to be done. Automation was in its infancy, so even on an assembly line you needed a massive number of people to put things together. It was still difficult and expensive to ship things around the world, so you needed people for your factories who lived close by, and the factories needed to be close to their customers. In the offices, the absence of things like copiers and computers meant huge pools of typists were necessary just to ensure that adequate copies of important documents were made, properly formatted.

By the 2000s, automation had progressed to the point that a huge number of workers were no longer needed in the factories. Manufacturing as a sector of the economy continues to outproduce China and to grow in real dollars, but jobs in manufacturing shrank from the 1970s through today.

Similar things happened to typists and secretaries, whose jobs were steadily cut by improved technology. Now even executives tend to type their own letters in word processors, and as many copies as they need are a couple of clicks away.

That's called efficiency, and it is a major reason that the US economy remains so much more productive than the rest of the world. Capital is cheaper than labor, so the investment of capital meant that profits rose as costs fell.

Profits, though, don't go to everyone. The benefits of automation are for the owners of the machines: the workers without jobs not only do not benefit, but are positively harmed.

In addition, the ease and cheapness of global shipping means that it is now feasible to make things abroad. Improvements in telecommunications make it easier still.

The upshot of all of this is that -- not to put too fine a point on it -- there's a lot less labor that needs to be done. There will be less labor needing to be done in the future.

For now that means persistently high unemployment. In the future, it means a day when we have to face the reality of permanent unemployment for a large part of the population.

That means rethinking our basic model about how we adjudicate resource distribution in America. For as long as the nation has been in existence, that was done in terms of their pay for employment.

It may have to be done differently in the future, and we don't have a good model. On the one hand, it is simply unreasonable to ask people who are permanently out of work to get by on nothing. They can't. On the other, direct payments from the government -- entitlements, that is -- have a soul-destroying quality when applied as welfare instead of retirement pay. This is true in Saudi Arabia, for example, where the massive wealth of the society is such that everyone gets a stipend. They all hire servants to do all the labor; but it somehow fails to be the happiest place on earth.

For the short term, we need to cut spending and entitlements; but for the long term, we need to look at new ways of raising revenue. There are good arguments against corporate taxes, though it seems fair to suggest that some of the benefits of the efficiency of automation should go to the people who are put out of work. It may also be the case that we need to look at ways of raising revenue from the world at large to help pay for the Navy that guards their trade lanes, thus providing a benefit to their nations as well as our own.

This is a pretty sticky problem. The only answer we've come up with so far is to make-work through bubbles: that is, since we don't need any more than we have, we'll spend money on things we just want. That got us many McMansions with tile kitchens, and for a while it paid for many construction workers; but it was never sustainable. We need a better answer.

MikeD's Avatar

MikeD gave an amusing take on his experience with reality simulations in our recent discussion. We laughed, but apparently this is the fellow you were simulating.

H/t: Al Fin.

Age-Appropriate Stupidity

Age-Appropriate Stupidity

Age-Appropriate StupidityI enjoyed Assistant Village Idiot's essay today about "kids today" and "kids yesterday." He suggests that these complaints suffer from the usual problems of nostalgia's rose-colored lenses. He also posits his pet theory that the most economical explanation of the social changes of the last century is that teenagers in the 50s acquired disposable income for the first time in history. This theory parallels the notion that obesity and other diseases of plenty are a result of millions of years of evolution amid scarce resources, suddenly confronting an embarrassment of riches that our genes aren't prepared for.

Almost my favorite part, though, was this comment quoting an exchange between the writer and his 13-year-old daughter:

D: When you get your license, our auto insurance costs will increase dramatically.

E: Why?

D: Because 16 year olds are stupid.

E: Thanks Dad.

D: Nothing personal. All 16 year olds are stupid. I was stupid when I was 16. It's just the nature of things.

E: Nothing personal?

D: No. And it may be small comfort to know that older people are also stupid. People are just stupid generally. The difference is that as you get older, the kind of stupidity changes. It tends to be less immediately life-threatening, and tends more toward the kind of stupidity that merely ruins your life -- or what's left of it. Insurance companies don't care about that.

That gave her something to chew on.

Class Warfare vs. Anti-Cronyism

Class Warfare vs. Anti-Cronyism

Class Warfare vs. Anti-CronyismLittle Miss Attila links to an article by Timothy P. Carney in the Washington Examiner about the current administration's consternation over the public's drawing the wrong conclusions from the distribution of wealth and poverty. The administration hoped that resentment of Wall Street fat cats would propel Democrats to a mid-term victory; instead, much of the voting public identified the Democratic leadership with back-room deals for the well-connected. Even worse, they identified the Republican insurgents with genuine populism. Similarly, the public was cool towards the revival of the estate tax, no matter how much it was touted as a blow against the "rich." At heart, the Democrats mistook a popular revulsion against cronyism for a hostility to wealth. As Carney says:

[C]ronyism -- not wealth -- is the object of today's populist ire. . . . The Left has misread the postbailout populist sentiment all along, assuming public anger was directed at the rich. But American anger, I suspect, is directed not at some people who have money or success, but at those who profit through cronyism and their connections to power. . . . . In other words, anti-bailout anger is not anger at the rich, but anger at those unfairly getting rich -- at the taxpayer's expense.

Carney concludes that the Left is drawing the wrong conclusion about the Wisconsin battle over public sector unions, even as the battle spreads to other states. Paul Krugman, for instance, asserts that government unions provide a "counterweight to the political power of big money." That assertion, of course, draws horselaughs from voters who have begun to open their ears to the conservative counterargument: public sector unions are the ultimate example of the political power of big money.

I grew up thinking the Democrats were the champions of the ordinary citizen against an over-powerful government. I switched to the Republican Party when I concluded they did a better job at that task. Nothing disgusts me more in a RINO than a desertion of conservative principles in favor of country-club cronyism; I don't like it any better than I like public-sector unions. So I'd like to see the new Republican House majority go after ethanol subsidies, for instance, and to dismantle every bit of the Spendulus Bill that's still standing.

Democrat or Republican, what stands between us and cronyism is the principle of limited government. We need to keep government from interfering constantly in the economy to reward the good guys and punish the bad guys with tax policy and stimulus spending. They have no reliable skill at distinguishing one from the other, and no business getting in the game at all.

Arendt & the Suicide

A woman I've been spending a lot of time with lately is Hannah Arendt, the author of Eichmann in Jerusalem, The Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition among other works. You may find this article about her interesting, as it treats her correspondence -- usually hostile -- with another Weimar-Republic thinker who resettled himself to Jerusalem after the war. It was occasioned by the suicide of a man named Walter Benjamin.

Best Presidents Evah

Best Presidents Evah

Best Presidents EvahI keep reading about the recent Gallup poll asking who was the greatest U.S. president. I believe Ann Althouse correctly explains the otherwise perplexing results:

[T]he main thing going on here is people are being asked to come up with the name of a President, and they don't have that many names floating around in their heads. It's always safe to say "Lincoln." Beyond that, they're rooting around in the decades they remember personally.Someone else suggested you might get more interesting results if you required people to give two reasons for each choice, then throw out the choices backed up by reasons that were obviously pulled out of thin air ("Like, he was the most awesome and saved the world and stuff").

But I'm more interested in the views on the subject I'm likely to find here. I believe my vote goes to Washington, for setting the example of a peaceful relinquishment of power in an age when it was practically unheard of. Frankly, even today, not many people worldwide can expect to enjoy that blessing in their lives. It's a signal achievement of the American experiment.

Stories I Like to Hear

Per the New York Post, Lara Logan credits Egyptian women with preventing her being raped, by piling their bodies on top of her. That's morality and courage in action: placing your vulnerable body between someone else and harm. You don't have to be big and strong to do it.

It seems she was more scourged than beaten. If she'd been beaten for half an hour, she'd be dead. Instead she's covered in painful welts, obviously inflicted in a desire to shame and intimidate her. That's one reason I'm encouraged to hear that women in the crowd took it on themselves to intervene. I would imagine that Ms. Logan formed a lifelong bond with them in that moment.

Whither Morality

Philosophy Now is hosting a series of articles defending various versions of the idea that we should dispense with morality as an idea. Unfortunately, aside from that introduction, only one of the articles is available for nonsubscribers, Dr. Jesse Prinz' suggestion that all morality is cultural. This is actually one of the weaker claims, in that there is still a place for morality at the end of the discussion: the stronger claims are that morality should be abandoned even as a concept.

Read it through, and let's discuss it. I am myself a moral realist, so I don't agree with any of the positions being argued; but I'll be glad to explore them with you, to see why they might be stronger than they appear, or to suggest why they might not finally be right.

Winning

So says E. J. Dionne, Jr., who notes:

Take five steps back and consider the nature of the political conversation in our nation's capital.... Washington is acting as if the only real problem the United States confronts is the budget deficit; the only test of leadership is whether the president is willing to make big cuts in programs that protect the elderly; and the largest threat to our prosperity comes from public employees.There are three separate assertions that concern us here.

...

The media are full of commentary on President Obama's "failure of leadership." There is some truth to the critique but not in the way the charge is typically made.

Obama is not at fault for his budget proposals.... In his State of the Union address, Obama made a good case that budget cutting is too small an agenda and that this is also a time for more government - yes, more government - in areas that would expand opportunities and strengthen the economy.

1) The national conversation has turned (thanks, perhaps, to the TEA Party) to the importance of cutting the costs of government, especially entitlements and payments to government workers.

2) The President believes that the fact is that we need more, not less, in terms of government spending and involvement.

3) The media is unfairly hurting him by framing this as a failure of leadership instead of an attempt to lead, but in the opposite direction.

Let's compare that with a news story from the NYT, on the President and the Wisconsin situation:

"Wisconsin Puts Obama Between Competing Desires"There's not much in the article to suggest that "deep spending cuts to reduce the debt" is actually a "desire" of the President's (nor even "projecting a message" in favor of such cuts). It does mention his two-year freeze on pay raises, but that is clearly not a deep cut.

The battle in Wisconsin over public employee unions has left President Obama facing a tricky balance between showing solidarity with longtime political supporters and projecting a message in favor of deep spending cuts to reduce the debt.

What it sounds like is that Mr. Dionne is right: the editors at the NYT are trying to "help" the President by portraying him as "leading" in a direction he doesn't want to go. In that way they may be hoping to shore him up against what they see as his own failure to understand and lead the national conversation; but they're masking his real attempts to lead in the other direction.

That's neither wise nor fair, even to President Obama. He was elected on a big-government platform, and it is clear that he believes in it, and has steadily argued for a larger government role in American society and the economy.

This is the political question of a generation for the United States of America: how to handle both the current economic disaster and the long-term problems of impossible entitlements, debt, and un- and under-funded government pensions. What we do now may save or doom us; the decisions made now will set a course that will be increasingly difficult to reverse by future governments should that course prove to be wrong.

Previous Congresses and administrations are at fault for us being here, by the same token: we wouldn't be facing these problems if they had not made promises to the sky on entitlements and pensions, while at the same time spending all the cash they were supposed to be saving up to pay for those promises.

Let's have the argument fairly. It may be that the TEA Party will win, or it may be that the President's party will win, but there is a clear difference between them.