From City Journal:

Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey are no more. Like Plessy v. Ferguson before them, Roe and Casey were constitutionally and morally indefensible from the day they were decided, yet they endured for generations, becoming the foundation of a mass political movement that did all it could to prevent their overruling. Thus, like the overruling of Plessy, the overruling of Roe and Casey was by no means inevitable; it was the result of a half-century of disciplined, persistent, and prudent political, legal, and religious effort. The victory in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization was earned by the coalition of teachers and students, priests and parishioners, lawyers and politicians, who, through efforts as humble as parish potlucks and as prominent as federal litigation, brought about the most important legal and human rights achievement in America since Brown v. Board of Education.

The analogy I would have thought more proper is to Dred Scott. The twin abortion decisions adopted a similar logic, after all: that there was a class of human beings, X, whose rights or interests another class of human beings, Y, did not have to respect. Rather, Y as a class was entitled to dispose of a member of X in whom they stood in the right kind of ownership relation in order to further their own interests. "My body, my choice" as a slogan disposes of the idea that there is another body to be considered, or another being: it asserts that only the one kind of being really exists or really matters.

All my life I have heard versions of the argument that only women should really be consulted about abortion: "No uterus, no opinion." Yet to accept this is to make a core philosophical error, one warned against since at least Aristotle: no one should serve as the judge in their own case. Women are of course very deeply interested in the disposition of this question of abortion rights. It is that very interest that makes it hard for them to render a just verdict, which by the nature of justice ought to be disinterested. The Viking-age hero Egil Skallagrimsson, offered the opportunity to judge in his own case, settled everything in favor of his family; here, everything was settled by class Y in the interest of class Y, and the interests of class X were completely obliterated. Abortion was acceptable all the way to the moment of birth, and arguments were increasingly being offered that it really ought to be acceptable even after.

Now the matter remains unsettled, but it is at least open to the people -- all the people, and not only the interested class -- to debate and consider how to proceed. This seems to me to be right and proper. In this matter I have no more say than any other citizen; I can offer philosophical accounts of what seems right, but each of you will have to judge and vote and advocate accordingly. It will doubtless be done in ways I think wrong, as is usually true on every question, because democracy depends on a common opinion and the opinions of most people are not generally given to philosophical rigor.

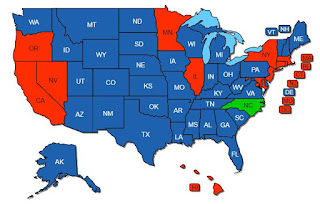

Yet at least it will be the common sense of communities that decides this question, and not that of an interested class or an elite among the judiciary. Perhaps few will prove to be truly disinterested; likely different communities will arrive at widely different judgments. Such is life. Justice is more likely, all the same, now that the matter is before the people broadly and not only the few.